In 1938, an old Dutch cemetery was demolished to make way for the expansion of the North Beach Airport—today’s LaGuardia Airport—in Queens. The small graveyard was situated on a bluff overlooking the waters of Bowery Bay, on land that had once been part of a vast estate established by Pieter Cornelisz Luyster in 1668. Pieter Luyster was a carpenter who emigrated from Holland in 1656 and was the progenitor of the Luyster family in America. After he died in 1695, the Luyster estate at Bowery Bay remained in the family for more than a century, each generation burying deceased relatives and friends in the hilltop burial ground.

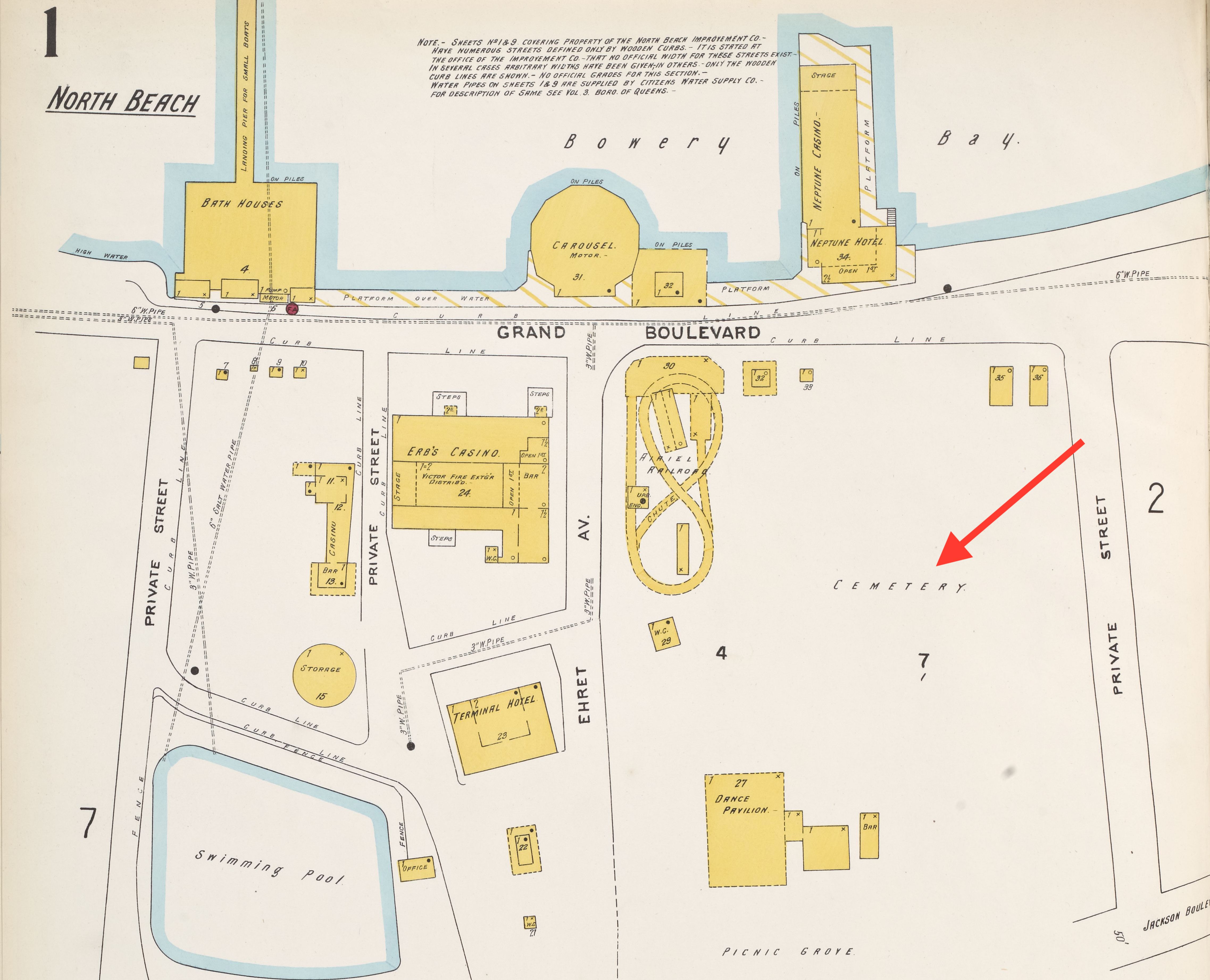

By the mid-1800s, the Luyster estate had been divided into half a dozen farms that passed into other hands. In the 1870s, piano manufacturer William Steinway partnered with brewer George Ehret to acquire a large section of the old Luyster lands along the shore of Bowery Bay and in 1886 opened a pleasure garden and beach there. Reaching its peak between 1895 and 1915, Bowery Bay Beach (later called North Beach) offered swimming and boating facilities, picnic grounds, and restaurants, as well as carousels, a Ferris wheel, roller coasters, and other attractions.

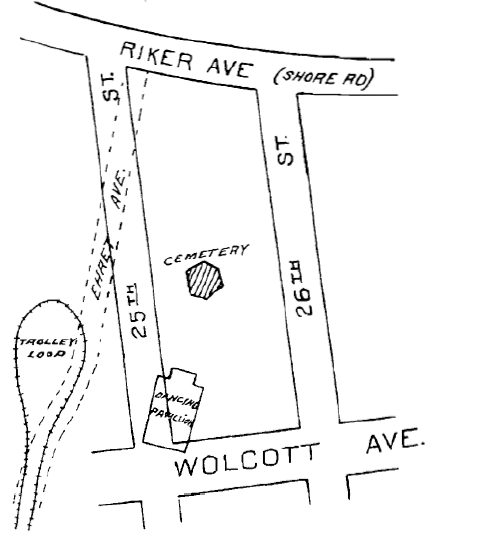

For decades, the Luyster Cemetery stood within this “Coney Island of Queens” and was frequently encountered by the recreation area’s visitors. Several early 20th-century newspaper articles describe the graveyard, which was a small square plot with apple trees at each corner offering protection to four rows of headstones. In 1903, the New York Times noted that the cemetery was between a roller coaster and a dance hall and that “picnickers camp among the stones and scatter their luncheon crumbs over the sod.”

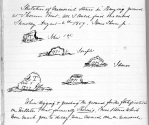

In 1919, the Queens Topographical Bureau recorded inscriptions found on the 36 headstones still present in the Luyster Cemetery at that time. Many of the headstones were brownstone, while some were of marble and others simply rough fieldstones marked only with initials and years of birth and death. The earliest identifiable grave in the burial ground was that of Mary Luyster Rapelye (1696-1732), a granddaughter of emigrant forefather Pieter Cornelisz Luyster. The latest was that of Martin Rapelye, who died at age 81 in 1816. Most of the tombstones marked the resting places of other members of the Luyster and Rapelye families.

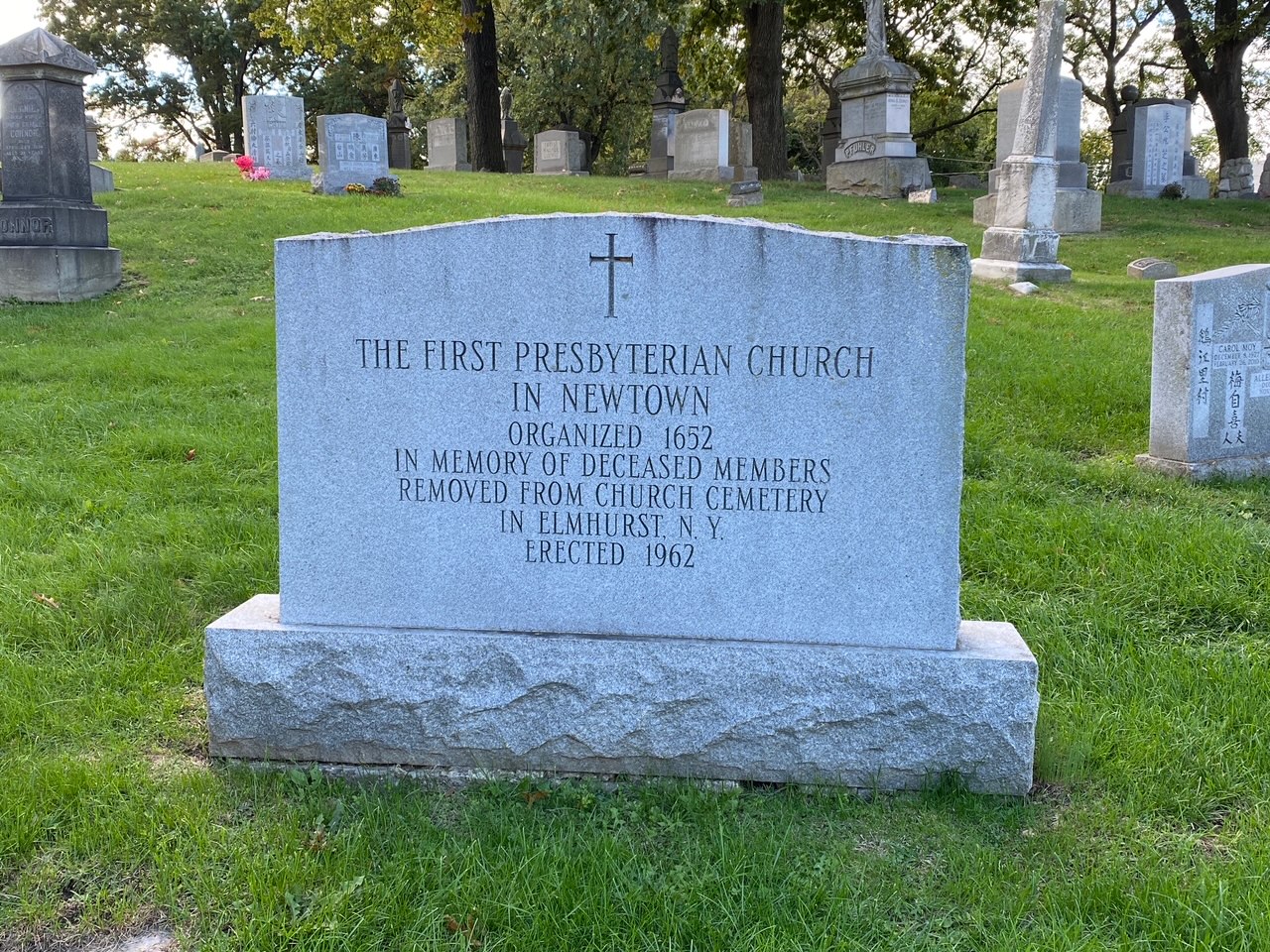

World War I and the passing of Prohibition in 1919 brought an end to the pleasure grounds at North Beach and by the 1930s the lonely little Luyster Cemetery stood among the the rotting structures that once housed its amusements. Before the area was redeveloped for the airport expansion in 1938, the Docks Commissioner arranged for the removal of the remains from the Luyster Cemetery to a plot at nearby St. Michael’s Cemetery. The last of the bodies were moved in May 1938. Today the former site of the Luyster Cemetery is near the west boundary of the LaGuardia Airport complex.

Sources: Sanborn’s 1903 Insurance Maps of the Borough of Queens, Vol 5 Pl 1; The Annals of Newtown (Riker 1852); History of Queens County (Munsell 1882); Description of Private and Family Cemeteries in the Borough of Queens (Powell & Meigs 1932); “The Luyster Burial Place,” Newtown Register, Jun 7, 1900; “Some Old Graves in North Beach,” Greenpoint Weekly Star, Aug 30, 1902; “Picnic in a Graveyard,” New York Times, Aug 3, 1903; “Graves Dug 200 Years Ago,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sep 28, 1907; “North Beach Pleasure Seekers Keep Sacred Old Graveyard of Rapelye and Luyster Families,” Daily Star (Long Island City, NY), Aug 1, 1924; “Old North Beach Resort to Become Part of New Jackson Heights Airport,” Daily Star (Long Island City, NY), Feb 5, 1929; “Old North Beach Burying Ground May Vanish to Make Way for Airport,” Daily Star (Long Island City, NY), Feb 7, 1929; “Old Cemetery to Be Dug Up,” Long Island Daiy Press, Apr 30, 1938; “At City Hall,” New York Post, May 4, 1938