In the early 1800s at least a dozen small burial grounds speckled the landscape of farms and estates across the six historical townships that came to form the modern borough of Brooklyn. These graveyards were set aside on homesteads of families that settled the area during the Dutch colonial period and later, and their owners tried to preserve them for descendants with covenants in wills and deeds that exempted them from property transfers. But as urban development encroached over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries and estates were broken up and sold off, most of these families—once prominent in local events and public life—disappeared from the area, as did their ancestral burial grounds. Today only one of these homestead burial grounds survives in Brooklyn—the tiny Barkeloo Cemetery in Bay Ridge.

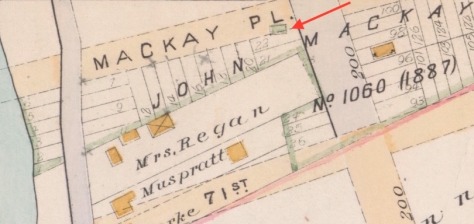

The Barkeloo family home stood on the Shore Road overlooking the Narrows and New York Bay, in the Yellow Hook section of the historic Town of New Utrecht. To the rear of the residence was the family burial plot, situated at what is now the corner of Narrows Avenue and MacKay Place. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Jaques Barkeloo (1747-1813) occupied the farm with his first wife Catharine Suydam (1753-1788), his second wife Maria Bogert (1768-1841), and offspring from both marriages. Jaques Barkeloo was a prominent figure in New Utrecht, serving as Town Supervisor for several years.

In 1834, the old Barkeloo homestead transferred out of the family when Jaques’ widow Maria sold the property. The graveyard was excluded from the deed and the family continued to make burials there until 1848. For many years thereafter, the burial ground was reportedly well cared for, surrounded by a high picket fence that was regularly given a fresh coat of white paint, and the branches of the family contributed annually to a fund for upkeep of the site. But by the end of the 19th century few Barkeloo descendants remained in Bay Ridge and their ancestral burial ground was neglected. In July 1897, the New York World reported that the spot was “unkept,” “surrounded by a dilapidated wooden fence,” and threatened by road construction. Though the site may have contained more than 30 graves, only three tombstones were standing at that time—those of Jaques Barkeloo, his first wife Catharine, and his widow Maria.

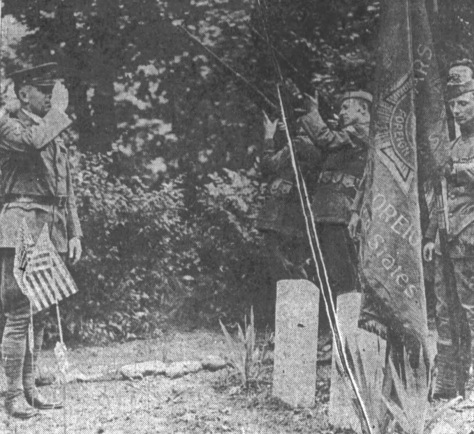

The Barkeloo family cemetery continued in a state of disrepair until 1923, when a local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution rehabilitated the site, clearing it of rubbish, covering it with new soil, and surrounded it with a hedge. By this time, Jaques Barkeloo’s tombstone had disappeared, but his wives’ tombstones remained, and another—that of Margetta Barkeloo Wardell (1798-1834)—was found buried four and a half feet under dirt during the landscaping work. As part of their efforts to revitalize the site, the DAR touted it as a Revolutionary War cemetery by installing a monument in honor of Harmanus Barkeloo (1745-1788), who in March 1776 was commissioned as Second Lieutenant in the New Utrecht Company of the Kings County Militia. Harmanus survived the war but was felled by smallpox when traveling in New Jersey in 1788; sources disagree as to whether he is interred in the Barkeloo Cemetery or at the Old Parsonage Burying Ground in Somerville, New Jersey.

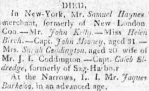

The DAR also installed a monument for Simon Cortelyou (1746-1828), who married Jaques Barkeloo’s widow, Maria, and is believed to be buried next to her in the Barkeloo cemetery. Cortelyou was “one of the many Tories who infested Long Island,” as one local history puts it; a well-known British loyalist, Cortelyou was imprisoned and fined for mistreatment of American prisoners during the Revolution. Given Cortelyou’s history, it’s curious that the DAR chose to memorialize him; however, when dedicating the rehabilitated cemetery, they claimed they had found records (possibly these) showing that Cortelyou gave “vast sums of money for Washington’s army” and that he had been in constant communication with Governor George Clinton during the war. Whatever the case may be regarding Cortelyou’s loyalties during the Revolution, he was a leading community figure in New Utrecht during the early Republic era and seems to have been forgiven any anti-patriotic sins of his past. His obituary, which ran in the New York Spectator on August 15, 1828, reads simply: “Died—On Friday night at the Narrows, L.I., Simon Cortelyou, Esq., an old and respectable inhabitant of that place.”

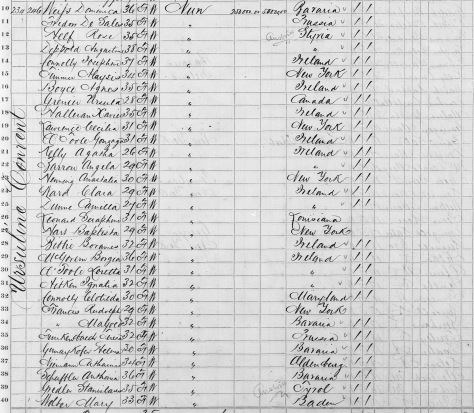

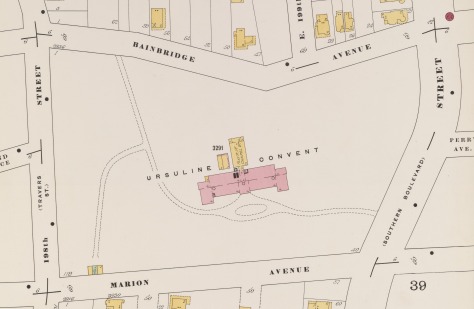

Now tucked behind Xaverian High School, which has occupied the former Barkeloo homestead since the 1950s, the Barkeloo Cemetery links the past of old New Utrecht and the American Revolution with the present Bay Ridge and the modern city that has been built around it. It endures through the efforts of various civic groups and neighborhood caretakers, who’ve protected the site with a wrought-iron fence and keep the grounds nicely maintained with pretty flowers and trimmed shrubbery. A large granite marker installed at the site in 1984 by the Trust of Emma J. Barkuloo and Bay Ridge Historical Society lists 21 people thought to be interred here.

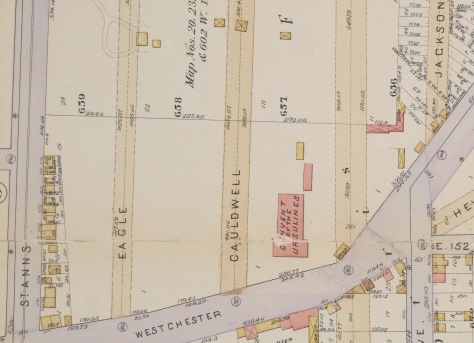

Sources: Eddy’s 1811 Map of the Country Thirty Miles Round the City of New York; Robinson’s 1890 Atlas of Kings Co. Pl 8; The Bergen Family or the Descendants of Hans Hansen Bergen (Bergen 1876), 375; History of Kings Co. (Stiles 1884), 263-266; Reminiscences of Old New Utrecht and Gowanus (Bangs 1912); Cemeteries in Kings and Queens Counties (Eardeley 1916), 1:47-48; Twenty-third Annual Report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, 1918, 285-286; “Wanted,” The Diary, May 22, 1793; “Died,” Long Island Star, Apr 14, 1813; “Sheriff’s Sale,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan 13, 1880; “An Old Cemetery to Go,” New York World, Jan 7, 1897; “Ancient Gravestones in Old Bay Ridge,” Brooklyn Standard Union, Jul 6, 1919; “Historic Old Burying Ground,” Brooklyn Standard Union, Nov 21, 1922; “DAR Will Restore Old Burial Plot,” Brooklyn Standard Union, Feb 4, 1923; “Honor Memory of Revolution Heroes Buried in Bay Ridge,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov 4, 1923; “Rescuing Brooklyn’s Tiniest Graveyard,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec 16, 1923; “Two Revolutionary War Heroes Made V.F.W. Members,” Brooklyn Times Union, Jul 23, 1926; “Shaft to Be Dedicated at Barkeloo Cemetery,” New York Daily News, May 1, 1935; “New Fence for Barkaloo Cemetery,” Home Reporter & Sunset News, Feb 8, 1980; “Cemetery Revamp,” Brooklyn Graphic, Mar 16, 2010; “How an Ancient Cemetery Survived in Bay Ridge,” Hey Ridge, Jun 4, 2018; The Smallest Cemetery in Brooklyn Has a Story, Brooklyn Ink, Oct 24, 2019