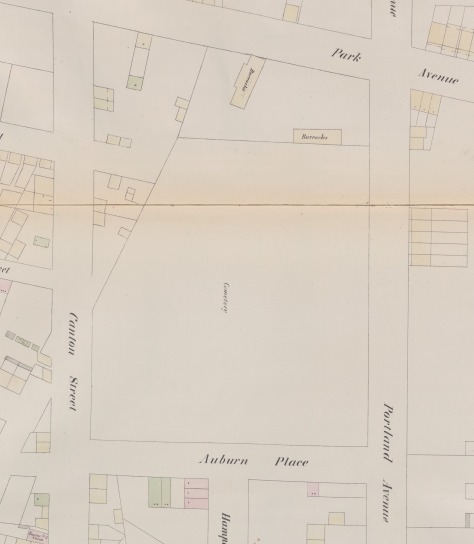

Just north of Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn is a site in the middle of the superblocks formed by the vast Whitman-Ingersoll public housing developments. Situated between St. Edwards Street, North Portland Avenue, Auburn Place, and Park Avenue, this site contains the Walt Whitman Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, P.S. 67/Charles A. Dorsey School, and the former Cumberland Hospital—the birthplace of sports greats Michael Jordan and Mike Tyson, now a homeless shelter and medical clinic. In the century before these institutions were erected here, this land was the Wallabout Cemetery, a public burial ground for the citizens of the City of Brooklyn.

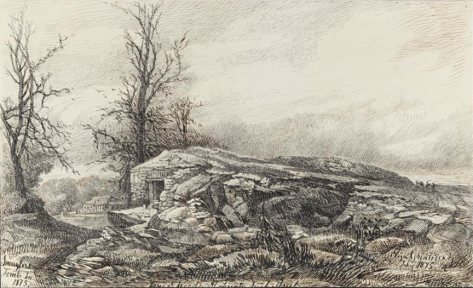

In the 1820s, the rapidly growing town (later city) of Brooklyn was running out of places to bury its dead. “Where shall I deposit the remains of my friend,” was a frequent question among the town’s citizens, according to the author of a letter published in the Long Island Star. The letter writer further commented that a survey of the “scanty burying grounds among us” was convincing evidence of the need for a public cemetery to be used by all denominations. In 1824 the town appointed a committee to find a suitable property for this purpose, eventually choosing five acres of farmland within a mile of the village, near Fort Greene and Wallabout Bay.

At a town meeting in April of 1827, the burial ground committee announced that preparation of the public cemetery was almost completed and that some graves had already been made in the allotments assigned to eight denominations—Reformed Dutch, Presbyterian, Methodist, Episcopal, Friends, Catholic, Baptist, and Universalist—and a ninth, common lot for use by the town for burial of the poor and those unaffiliated with a church. “The different allotments are separated and ornamented with forest trees,” the committee reported, “the fences and gateway are of solid masonry and the passage and road in front of the passage is paved.” Their report on the cemetery further boasts that “no place in the town is now more eligibly situated and better prepared for the purposes of interment, and that it probably contains space enough for each of our citizens who are journeying to this grave yard for a century to come; and that the work will remain a lasting monument of credit to this town.”

Despite these lofty aspirations, a mere 10 years later the Long Island Star lamented that Wallabout Cemetery “is shamefully neglected by its keepers, if such it have, and the cattle, horses and hogs have been allowed to break over its enclosure.” Upkeep of the public cemetery was an ongoing problem, evidenced by regular newspaper reports of its poor condition. In 1849, burials were disturbed when Canton Street (now St. Edwards Street) was constructed along the cemetery’s west side; a year later, the city’s Board of Health reported that Wallabout Cemetery was “densely crowded with bodies” and recommended its closure.

The City of Brooklyn finally closed the cemetery in 1854. In 1857 the state legislature passed a bill authorizing sale of the land and providing for burial plots for each denomination in the new, large cemeteries that opened in Brooklyn and Queens in the mid-19th century. Churches were responsible for removing the remains from their allotments, a process that took several years. In January 1861, Brooklyn Mayor Samuel S. Powell reported that the last of the remains had been removed from the Wallabout Cemetery and deposited in a plot acquired by the city at Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn.

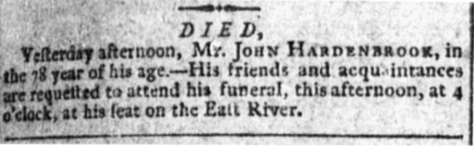

As with many 19th-century cemetery removals, some graves in the Wallabout Cemetery were missed during the process and encountered during later construction. In 1867 laborers digging for a cellar on the former cemetery site exhumed a coffin containing human remains; the inscription on the coffin plate was John Switzer, who died in June 1846. Many years later, in March 1924, workers for the Brooklyn Edison Company found human bones when excavating for a conduit at St. Edwards Street along what had been the western boundary of the former cemetery. The bones were reportedly “of both sexes, one wrist bone decorated with a bracelet or arm band of crude iron.” Remains of other 19th-century Brooklynites that may have been overlooked during the removal of Wallabout Cemetery possibly rest today beneath the grounds of the public institutions built on the site in the early 20th century.

Sources: Martin’s 1834 Map of Brooklyn, Kings County, Long Island ; Perris’ 1855 Maps of the City of Brooklyn, Pl 20; Laws of the State of New York, Passed at the 81st Session of the Legislature, Begun January 5th and Ended April 19th, 1858, Chap. 232; “Report,” Long Island Star, Jun 16, 1824; [Letter to Editor—Public Cemetery], Long Island Star, Jan 5, 1825; “Town Meeting,” Long Island Star, Apr 5, 1827; “Brooklyn Cemetery,” Long Island Star, Jul, 30, 1835; “The Violated Grave,” Long Island Star, Jan 11, 1838; “Common Council,” Long Island Star, Dec 30, 1839; “Common Council,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Nov 24, 1841; “The Burial Ground, Once More,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan 28, 1844; “Burial Grounds,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Oct 24, 1846; “Cemetery at the Wallabout,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Nov 9, 1849; “The Mayor’s Communication of the Wallabout Cemetery,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Nov 16, 1849; “Common Council,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Jan 22, 1850; “Removal of Dead Bodies,” Brooklyn Evening Star, May 22, 1850; “Public Notice,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Jul 24, 1854; “Things at Albany,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Mar 20, 1856; “New York Legislature,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Jan 26, 1857; “Notice to Episcopalians,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Aug 10, 1857; “Office of the Commissioners for Sale of the Burial Ground at the Wallabout,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Dec 15, 1857; “Wallabout Burying Ground,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Apr 27, 1858; “Great Sale of 11th Ward Property,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Jun 8, 1858; “Burial of the Dead,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb 17, 1860; “Common Council Proceedings,” Brooklyn Evening Star, Jan 29, 1861; “Human Remains Found,” Commercial Advertiser, Oct 14, 1867; “Thinks Old Skeletons Are From Ancient Cemetery,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Mar 25, 1924; NYC Then&Now