The Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan is the busiest bus station in the world, with a quarter of a million commuters and intercity passengers arriving or departing via 8,000 buses on a typical weekday. Located on Eighth Avenue between 40th and 42nd streets in Midtown, the terminal has a unique ramp system that provides a direct connection to the Lincoln Tunnel. These ramps are built over the site where the 41st Street Reformed Presbyterian Church Cemetery once existed.

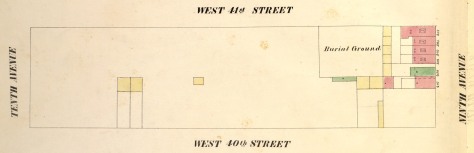

The Reformed Presbyterian Church Cemetery, approximately 125 feet wide and 100 feet deep, was located 100 feet west of Ninth Avenue on the south side of West 41st Street. The property was acquired for use as a burial ground in 1832, by three elders of the Reformed Presbyterian Church. The Reformed Presbyterian Church is a small denomination that originated in Scotland in 1690 when its members refused to become part of the national Church of Scotland.

The first Reformed Presbyterian congregation in New York City was organized in 1797 and had a church on Chambers Street in downtown Manhattan; in 1830 members living further uptown incorporated as the Second Reformed Presbyterian congregation and acquired a church at 166 Waverly Street in Greenwich Village; in 1848, part of this congregation split to form the Third Reformed Presbyterian congregation. After the 1848 split, the Third congregation remained at the Waverly Street location while the Second congregation erected a church on 11th Street near Sixth Avenue. Records show the 41st Street cemetery was used by both the Second and Third Reformed Presbyterian congregations, which collectively had about 500 members.

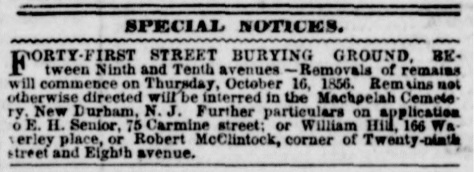

No records have been found to tell us how many people were interred in the Reformed Presbyterian Cemetery on 41st Street, or the names of those who were laid to rest there during the two-and-a-half decades it was utilized for burials. In October of 1856, church trustees removed the remains of those interred in the 41st Street burial ground to Machpelah Cemetery in what is now North Bergen, New Jersey.

In 1858, the Trustees of the Second and Third Reformed Presbyterian congregations sold the cemetery property and it was redeveloped. In 1890, the location of the former cemetery was occupied by a rag warehouse and other structures. Construction of the Port Authority Bus Terminal began in the late 1940s. Today, the piers supporting the ramp system, and several buildings beneath the ramps, stand on the former site of the 41st Street Reformed Presbyterian Cemetery.

Sources: Dripps’ 1852 Map of the City of New-York extending northward to Fiftieth St; Perris’ 1854 Maps of the City of New York, Vol 7 Pl 97; “Special Notices,” New York Herald, Oct 10, 1856; “City Items—A Burying Ground Closed,” New York Daily Tribune, Oct 16, 1856; “City Intelligence—Removing the Dead,” New York Herald, Oct 17, 1856; History of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in America (Glasgow 1888); Archaeological Documentary Study, No. 7 Line Extension/Hudson Yards Rezoning (Parsons Brinckerhoff et al 2004); “Prepare for Death and Follow Me:”An Archaeological Survey of the Historic Period Cemeteries of New York City (Meade 2020); “A New Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York,” TR News 31 Nov-Dec 2017; “Port Authority Bus Terminal to Receive Multi-Billion-Dollar Overhaul in Midtown Manhattan,” New York YIMBY, Feb 1, 2021