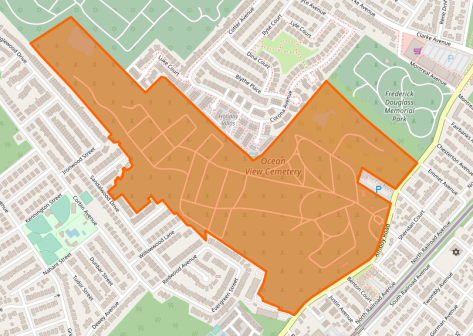

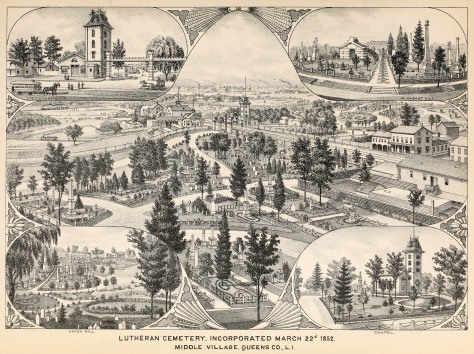

Lutheran Cemetery is one of over a dozen cemeteries developed along the Brooklyn-Queens border after the New York legislature passed the Rural Cemetery Act in 1847, spurring the creation of new large-scale cemeteries throughout the state. Founded in 1850 by the United Lutheran Churches of New York and incorporated in 1852, the cemetery was envisioned by Reverend F.W. Geissenhainer (1797-1879) when pastor of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church on Sixth Avenue and Fifteenth Street in Manhattan.

Through Dr. Geissenhainer’s efforts, and largely at his own personal cost, Lutheran Cemetery at Middle Village was established as an open, non-sectarian burial place where graves would be sold at affordable prices so that they could be available to people of limited means. By the 1880s, nearly 200,000 internments had been made in Lutheran Cemetery’s 225 acres and it was one of the busiest cemeteries in the vicinity of New York, averaging 12,000 interments each year. On Sundays, thousands of visitors took to the cemetery’s handsome, undulating grounds that included Trinity Lutheran Church, a chapel that was situated on a knoll in the south section of the cemetery.

Although Lutheran Cemetery has always welcomed people from all religious denominations, it was primarily patronized by the city’s German Protestant population during its early period. At the turn of the 20th century, it was the metropolis’ leading German burial ground and today the cemetery’s older tombstones bear this out in their strong Northern European character and German surnames. Epitaphs, often in the German language and written in Gothic script, speak of great loss, sorrow, and a desire for peace.

Lutheran Cemetery was not only the favored place for the city’s German Americans to be laid to rest, it was also a preferred spot to take their own lives. German immigrants were unusually suicidal during the 19th century—so much so that American economist and statistician Francis A. Walker called them “the great suiciding people among us.” Writing in 1875 about this phenomenon among German Americans, Walker noted that “one half of all the suicides which take place among the entire population are accredited to them.” Historical newspaper coverage reveals that over two dozen people committed suicide on the grounds of Lutheran Cemetery during the first 50 years of its history. Among them were Wilhelm Fuhlmer, a 26-year-old German tailor who in 1851 shot himself in the head on the grave of the wife of his grave and only child; Christopher Kunzman, who threw himself on a grave and slit his throat with a knife in 1872; and Frances Wittstadt, who poisoned herself on her husband’s grave in 1897.

Another tragic chapter in the history of the city’s German community is documented by the Slocum Monument situated in the south section of Lutheran Cemetery. The monument commemorates the 1,021 lives that were lost when the General Slocum steamboat caught fire and sank in the East River on June 15, 1904. Most of the passengers on board were members of St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, located in the area known as Little Germany on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

The burning of the Slocum was New York City’s deadliest disaster until September 11, 2001, and the extensive loss of life led to the disintegration of the Lower East Side’s German community. Many of the Slocum victims were interred in private plots at Lutheran Cemetery and another 61 unidentified victims were interred in the common plot where the Slocum Monument stands. Though marking the burial place of the unidentified dead, the towering granite monument was intended to stand as an overall memorial of the disaster. It was unveiled on June 15, 1905, and an annual memorial service for the victims has been held at the monument every year since that date.

The Slocum Monument has long been the main historical attraction at Lutheran Cemetery, but recent events have raised interest in another spot here—the Trump family gravesite. Cemetery officials don’t disclose the location to the visitors, but forensic investigation will lead the determined explorer to the plot (hint: it’s near the cemetery’s southernmost boundary). Marked by a modest granite monument, it is the final resting place of former President Donald Trump’s paternal grandparents (Fred and Elizabeth), his parents (Fred and Mary), and his eldest brother, Fred Jr.

The historic Lutheran Cemetery now has over half a million interments and is known as “All Faiths Cemetery,” the result of a 1990 rebranding that was meant to better reflect the cemetery’s non-denominational status and the demographical and cultural shift in the communities it serves. The cemetery’s German clientele has disappeared as those families moved away and its newer graves and visitors reflect the eclectic mix of Latino, Slavic, and Asian families that have settled in the area in recent decades.

View more photos of Lutheran / All Faiths Cemetery

Sources: The Cemeteries of New York (Judson 1881); History of Queens County (Munsell 1882); “With the Dead,” Brooklyn Times Union, Sep 14, 1888; The Leonard Manual of the Cemeteries of New York and Vicinity (1901); “Where Death Follows Death,” Newsday, Apr 20, 1988; “Occupations and Mortality of Our Foreign Population, 1870” Chicago Advance, Nov 12, Dec 10, 1874 and Jan 14, 1875. Reprinted in Discussions in Economics and Statistics (Walker 1899); “Dreadful Suicide,” New York Spectator, Aug 28, 1851; “A Dramatic Suicide,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb 20 1872; “All Were Weary of Life,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct 19, 1897; “Many More Buried,” New York Times, Jun 21, 1904; “The Slocum Disaster. Monument for the Grave of the Unidentified Dead,” New York Tribune, Mar 5, 1905; “Infant Unveils Shaft,” New York Tribune, Jun 16, 1905; “A Spectacle of Horror—The Burning of the General Slocum,” Smithsonian Magazine, Feb 21, 2012; “Annual Memorial Service for Victims of General Slocum Tragedy,” Queens Gazette, Jun 27, 2018. “Tommy Hadziutko Marks 50 Years Working at All Faiths Cemetery in Queens,” Daily News, Dec 1, 2011; Queens Historical Society Walking Tour of Lutheran Cemetery, June 6, 2011; Our History – All Faiths Cemetery; All Faiths Cemetery Walk, November 6th 2020; OpenStreetMap