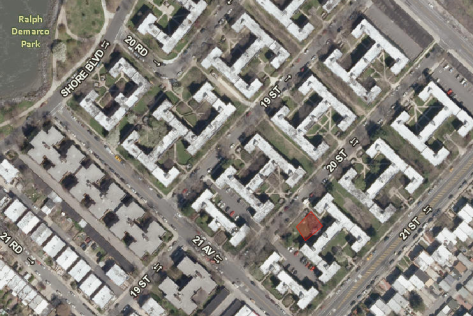

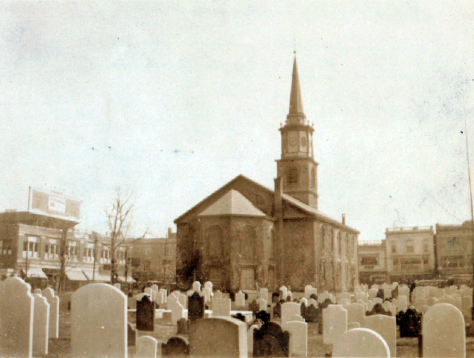

St. Peter’s Cemetery is the oldest Catholic burial ground on Staten Island, founded in 1848 by its namesake parish. The first Catholic parish on Staten Island, St. Peter’s was established at New Brighton in 1839, and the congregation built their church on a plot of land overlooking the Upper New York Bay. Soon after completing their church, St. Peter’s parish bought about three acres of land on the west side of Clove Road, in West New Brighton, for burial purposes. As graves filled, St. Peter’s Cemetery expanded in 1878 with the acquisition of three additional acres and again in 1898, when the parish purchased five acres on the opposite side of Clove Road for new graves. The grounds on both sides of Clove Road were further enlarged during the 20th century to bring St. Peter’s Cemetery to a total of 25 acres of burial space, holding 50,000 graves.

Some prominent figures are laid to rest at St. Peter’s Cemetery, including Civil War general Patrick Henry Jones, early baseball player Matty McIntyre, champion boxer Frankie Genaro, World War II Medal of Honor recipient Joseph F. Merrell, and three Staten Island borough presidents. Most notably, there is the grave of Father Vincent Capodanno, currently a candidate for sainthood. A U.S. Navy chaplain killed during the Vietnam War, Father Capodanno was struck down by a burst of machine-gun fire while attempting to aid and assist a mortally wounded Marine corpsman during heavy fighting on September 4, 1967. In 1969 he was a posthumous recipient of the Medal of Honor, and in 2006 was declared a Servant of God, the first step in the canonization process. Father Capodanno’s resting place at St. Peter’s Cemetery is now a pilgrimage site for Staten Island’s Catholic community. Here believers pray at the modest granite headstone marking the Capodanno family plot, and ask for the help and protection of the fearless “grunt padre.”

View more photos of St. Peter’s Cemetery

Sources: Butler’s 1853 Map of Staten Island; Bromley’s 1917 Atlas of New York City, Borough of Richmond, Pl 26; The Catholic Cemeteries of New York,” Historical Records and Studies 1; The Leonard Manual of the Cemeteries of New York and Vicinity (1901); Fairchild Cemetery Manual (1910); Realms of History: The Cemeteries of Staten Island (Salmon 2006); St. Peter’s Parish History (St. Peter, St. Paul & Assumption Parish); Patrick Henry Jones: Irish American, Civil War General, and Gilded Age Politician (Dunkelman 2015); “The Story of Matty McIntyre, Ty Cobb, and an Old-Time Baseball Feud,” Staten Island Advance, Jan 3, 2019; “50 Must-Dos for Boxing Fans,” Boxing News, May 23, 2019; “Obituary—Pfc. Joseph F. Merrell Jr.,” Daily News, Jul 23, 1948; “M’Cormack Pallbearers,”Brooklyn Times Union, Jul 13, 1915; “Staten Island Mourns as President Cahill is Buried,” Daily News, Jul 18, 1922; “Obituary—Cornelius A. Hall,” Daily News, Mar 10, 1953; “Obituary—Rev. Vincent Cappodano,” Daily News, Sep 16, 1967; “Remembering Father Vincent Capodanno,” Staten Island Advance, Sep 4, 2020; Father Capodanno Guild