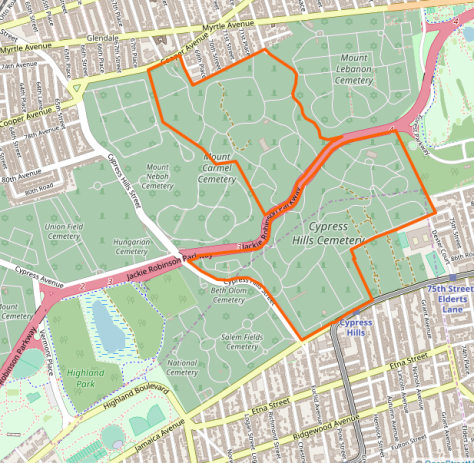

One of the city’s largest Jewish burial grounds is Montefiore Cemetery, located in far southeastern Queens near the edge of the New York City limits. This 114-acre site is situated on flat land along Springfield Boulevard and Francis Lewis Boulevard in Cambria Heights, an area that held a thriving Jewish population during the first half of the 20th century, and surrounds the non-sectarian, 5.5-acre colonial-era Old Springfield Cemetery on Springfield Boulevard.

Montefiore Cemetery has been serving the Jewish community of the New York City area since 1908, and hundreds of societies, congregations, lodges, and temples own sections here. Montefiore is the final resting place of more than 158,000 individuals, mostly ordinary men and women who are remembered with modest monuments that hint at life stories or personalities.“When we fell in love it was forever,” proclaims the inscription on one couple’s tombstone, while the numerous stones placed atop the marker of an “Adoring Grandmother / Beautiful Soul” attest to frequent visits and devotion of her family and friends.

A number of famous—and infamous—figures are also buried here, including abstract expressionist painter Barnett Newman, songwriter Sholom Secunda, actor Fyvush Finkel, and Prohibition-era mobsters Jacob Shapiro and the Amberg brothers, Hyman, Joseph and Louis. Prizefighter Al “Bummy” Davis (Albert Davidoff), who was killed resisting a Brooklyn bar robbery in 1945, is also here, as is Arnold Schuster, a 24-year-old clothing salesman who provided a tip that led to the capture of bank robber Willie Sutton in 1952 and was murdered a few weeks later, allegedly at the order of mob boss Albert Anastasia.

Most notably there is also the grave of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh—and last—leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic dynasty based in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Known universally as “the Rebbe” and considered one of the most influential Jewish leaders of the 20th century, Rabbi Schneerson died at age 92 in 1994. Every year, tens of thousands of Jews from around the world, many of whom claim Schneerson as the messiah, visit his gravesite. Following the belief that part of the soul of a righteous Jew who has died remains at the grave, when people visit they experience it as though they are in the presence of the holy man himself. When the Rebbe was of this world, people would visit him and write to him to ask for his blessing and advice. Now people visit the site where he is buried and leave little notes to ask for his blessing, informing him of recent activities, and asking questions—certain that the Rebbe will find a way to answer them. The notes are read at graveside, torn into four parts, and left on the ground in front of the grave.

Rabbi Schneerson’s grave is located in the northeastern section of Montefiore Cemetery where it borders Francis Lewis Boulevard. Shortly after the Rebbe’s death, Chabad Lubavitch purchased a house adjoining his gravesite. The site is known as the Ohel, and refers to the structure built around the resting place; the house abutting the cemetery is the Ohel Chabad Lubavitch Center, and offers access to the gravesite via a private walkway. Open day and night, all year, the Rebbe’s resting place has become a pilgrimage site for the ultra-Orthodox Lubavitchers, as well as for secular Jews and Gentiles who are drawn to the mystical passion surrounding the Rebbe. More than 50,000 people visited the site to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Rebbe’s death in 2014.

View more photos of Montefiore Cemetery

Sources: Montefiore Cemetery; [Montefiore Cemetery Ad], The American Hebrew & Jewish Messenger May 13, 1910, 40; “If You’re Thinking of Living In/Cambria Heights, Queens,” New York Times March 25, 2001; The Neighborhoods of Queens (Copquin 2009), 20, 189; Beyond the Grave: Cultures of Queens Cemeteries (Harlow 1997); “Thousands Beat Path to Queens Cemetery to Remember a Jewish Leader,” New York Times July 1, 2014; “Jews Make a Pilgrimage to a Grand Rebbe’s Grave,” New York Times Sept 13, 2013; OpenStreetMap