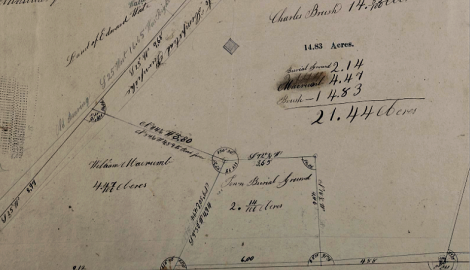

Beginning in the 1860s, cemetery corporations began to acquire tracts of land near Jamaica Bay to create what would become three Jewish cemeteries situated in today’s Ozone Park, Queens. Jointly, these cemeteries—Bayside Cemetery, Mokom Sholom Cemetery, and Acacia Cemetery—now cover close to 40 acres where an estimated 50,000 individuals have been interred. The adjoined burial grounds are located on flat terrain extending from 80th Street to 84th Street and from Liberty Avenue to Pitkin Avenue.

The cemeteries are separate, but their conterminous nature has frequently led to mix-ups in burial records, obituaries, and other accounts regarding which cemetery an individual was actually interred in. Newspaper reports and property records often confuse the cemeteries and their ownership as well. The three cemeteries also share a troubled record of poor stewardship, financial woes, chronic neglect and vandalism, and some of the most appalling acts of desecration ever to occur in New York City cemeteries.

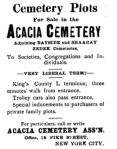

Bayside Cemetery (founded 1861), Mokom Sholom Cemetery (founded 1864), and Acacia Cemetery (founded 1896) each were established by independent corporations authorized by the state’s Rural Cemetery Act of 1847. The corporations acquired the cemetery land, which they then sold as sections or plots to hundreds of different Jewish burial societies, fraternal organizations, congregations, and other communal groups. Although family and individual plots also were sold, the majority of the cemeteries’ land was acquired by communal organizations who were responsible for the care and upkeep of their burial grounds.

Nearly all the organizations that purchased burial grounds at the three cemeteries were defunct by the mid-20th century, and few made financial arrangements to fund ongoing maintenance of their plots. Compounding this situation, the managing corporations who originally established the cemeteries also had become defunct over time, and responsibility transferred to Jewish congregations that had existing relationships with the original corporations. These congregations, which numbered around a thousand worshippers during their heyday, dwindled to just a handful of active members and lacked the resources to maintain the cemeteries.

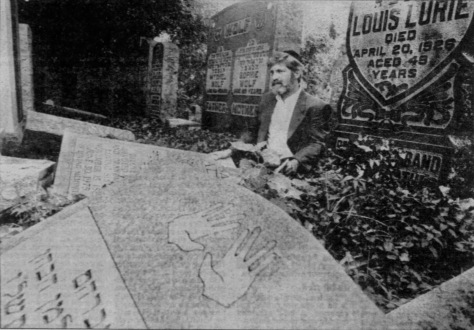

With insufficient resources for upkeep and monitoring of the burial grounds, the cemeteries deteriorated and became consistent targets for a wide range of intruders, including thrill-seeking teenagers, vandals, and thieves. Incidents were particularly rampant at Bayside and Mokom Sholom during the last decades of the 20th century (though Acacia also experienced occasional vandalism, incidences were not as frequent or severe).

In 1973, the National Guard were called in to help with clean-up and repairs at Bayside Cemetery, after a four‐year siege of vandalism in which hundreds of tombstones were overturned or broken, mausoleums smashed, iron gates ripped open, and the cemetery office building looted and ransacked. Between 1976 and 1978, over 500 tombstones were overturned at Mokom Sholom Cemetery. In addition to the pervasive vandalism that continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the cemeteries were frequently preyed upon by professional thieves who stripped dozens of mausoleums of their bronze doors, stained-glass windows, and marble interiors.

Acts of desecration at these cemeteries have gone far beyond vandalism and theft. In April 1981, a group of teenagers broke into a mausoleum at Mokom Sholom, pulled a coffin from its niche, smashed it open and drove a metal spike through the heart of the corpse. The perpetrators, who placed a dead cat above the body and a red candle nearby, were later caught while showing off Polaroid snapshots to a friend. In the twilight hours of Mother’s Day 1983, two young men viciously and methodically desecrated the grounds at Bayside Cemetery, smashing stained-glass windows and covering walls and tombstones with graffiti. In one mausoleum, they broke through a three-inch-thick marble floor and into the crypt of a girl buried there, at the age of three, in 1903. Dragging the tiny coffin out onto the roadway, they scattered the child’s remains, then took a rock and shattered the corpse’s skull. Another incident at Bayside was called “a pretty sick and perverted act” by Mayor Rudy Giuliani in June 1997 when “sickos” broke into a mausoleum and set fire to one of bodies, incinerating it so thoroughly that nothing remained but ashes.

These shocking episodes of vandalism and desecration have decreased in recent years, as steps were taken to secure the cemeteries and provide them with the attention they needed. Mokom Sholom and Acacia, which had been owned by Manhattan’s Congregation Darech Amuno and Pike Street Synagogue, respectively, were taken over by the state in the 1970s and placed in receivership; today both are administered by David Jacobson, who operates several of the city’s smaller Jewish burial grounds. Bayside Cemetery, which is owned by Congregation Shaare Zedek of Manhattan, has continued in a serious state of disrepair. Other than the efforts of dedicated volunteers who labored for years to restore dignity at Bayside, the cemetery had essentially been abandoned until recently. In 2017, Shaare Zedek reached an agreement with the state Attorney General’s office to dedicate $8 million dollars from the sale of their Upper West Side synagogue for long-term care of Bayside Cemetery; rehabilitation efforts began in 2018.

It’s unfortunate that the history of these cemeteries—and the stories of those interred within their grounds—has been overshadowed by a depressing saga of neglect and desecration. Family visitors are few, and there are no graves of famous individuals to attract much public interest in these burial grounds (though a US Congressman and a Titanic victim are interred at Bayside). Still, it’s worth remembering that Mokom Sholom means “place of peace” and Bayside was so named because various small streams leading in from nearby Jamaica Bay came up to its boundaries before modern development encroached. When wandering in the secluded urban wilderness of these cemeteries today, it’s easy to imagine this was once a lovely spot, where thousands of Jewish New Yorkers were laid to rest as the sea breezes swept in from Jamaica Bay.

View more photos of Bayside Cemetery

View more photos of Mokom Sholom Cemetery

View more photos of Acacia Cemetery

Sources: Dripps 1872 Map of Kings County, with parts of Westchester, Queens, New York & Richmond; The Leonard Manual of the Cemeteries of New York and Vicinity (1901), 9, 11-12; Fairchild Cemetery Manual (1910), 12, 17; “Notice,” Long Island Farmer Apr 2, 1861; “To the Jewish Public,” Jewish Messenger, Sep 18, 1861; “Notice,” Long Island Farmer, Feb 9, 1864; “Notice,” Jewish Messenger, May 6, 1864; “Proposed New Cemetery,” The Journal, Mar 21, 1896; “Cemetery Plots for Sale,” American Hebrew, Mar 10, 1899; “Restoring Dignity to Cemetery, Daily News, May 21, 1973; “Vandalism Is on the Increase in City’s Cemeteries,” NY Times, Dec 18, 1973; “NY State Takes Over Ozone Park Cemetery,” The Wave, Aug 20 1977; “Vandals Attack Cemetery,” Daily News, Dec 4 1978; “Corpse in Mausoleum Desecrated by Vandals,” NY Times, Apr 3, 1981; “In New York, Not Even the Dead are Safe,” Daily News Sunday Magazine, Aug 21, 1983; “Vandals Rock Jewish Cemeteries,” Daily News, Sep 9, 1991; “Cemetary[sic] Vandalized,” The Journal News, Apr 6, 1994; “3 Cemeteries are Haunted by Vandals,” NY Times, Nov 24, 1996; “An Affront To the Dead, And the Living, NY Times, Jun 13, 1997; “Resting—But Not in Peace,” Daily News, Oct 12, 1997; “Can a Catholic Guy Save this ‘Hellhole’ Jewish Cemetery?” Forward, Jun 10, 2018; Kroth v. Chebra Ukadisha, 105 Misc. 2d 904 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1980); International Jewish Cemetery Project—Queens—Ozone Park; Congregation Shaare Zedek—Cemetery FAQs