In 1845, a group of about 50 English and Dutch members of B’nai Jeshurun seceded from the synagogue to form Congregation Shaaray Tefila (Gates of Prayer). Shaaray Tefila built their first synagogue in 1846 on Wooster Street and continues today at their present temple on 79th Street in the Upper East Side.

The first concern of the new organization was the purchase of property for a burial ground and in January of 1846—before Shaaray Tefila was yet legally incorporated—two founding members, Morland Micholl and John I. Hart (both former presidents of B’nai Jeshurun) acquired land for this purpose. Situated on the south side of 46th Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues, the property purchased by Micholl and Hart was quickly found not to be suitable for burials and was resold. On November 24, 1846, Louis Levy (Shaaray Tefila’s first president) purchased another parcel, on 105th Street near Fifth Avenue, that would go on to serve as Shaaray Tefila’s cemetery for the next decade. Levy transferred ownership of the property to the congregation when they received their charter in 1848.

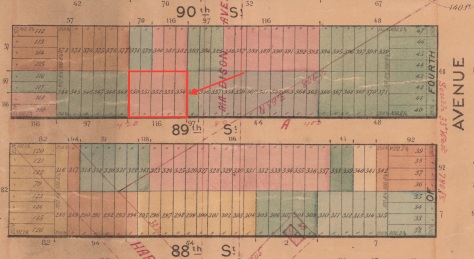

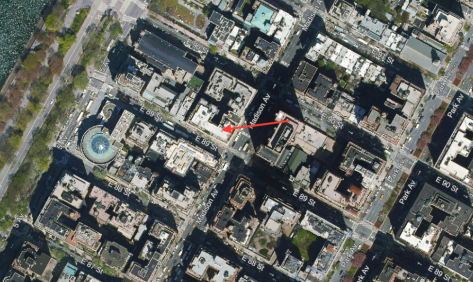

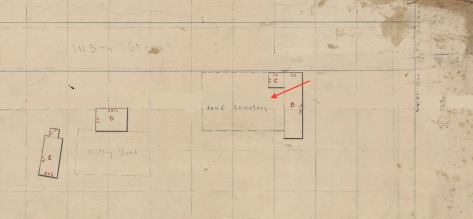

Shaaray Tefila’s cemetery was located on the south side of 105th Street, west of Fifth Avenue, at the north end of today’s Central Park. The burial ground, 100 x 100 feet, was in the area now part of the Conservatory Garden. Just west of the former cemetery site is the Mount, where the Sisters of Charity established the religious community of Mount St. Vincent in 1847. Construction of Central Park forced both the Sisters of Charity and Shaaray Tefila to abandon their properties here. In 1856, Shaaray Tefila purchased a portion of the land held by its parent congregation, B’nai Jeshurun, at Beth Olam Cemetery in the Cypress Hills area of Brooklyn, and the two congregations decided to administer their burial grounds together. Remains from Shaaray Tefila’s 105th Street Cemetery were removed to their new burial ground at Beth Olam in 1857, at “very heavy expense to the Congregation,” according to an auditor’s report from June of that year.

It is not known how many members of Shaaray Tefila were interred in the 105th Street cemetery before its closure, but among their number was founding member Morland Micholl (mentioned above). A native of Chesham, England, Micholl was interred at the 105th Street cemetery when he died of a “short and severe illness” at age 56 in 1853. He was a prominent member of the city’s Jewish community for 30 years, and his obituary in The Asmonean asserts “his integrity as a merchant, his uprightness as a citizen, his piety as a religionist, and his charity as a man.” Friends of the late Mr. Micholl assembled at the 105th Street cemetery on October 29, 1854, to dedicate his monument—a 10-foot-tall marble obelisk that faced the cemetery’s entrance. Micholl’s monument would stand for just a few years before the cemetery’s removal to Beth Olam, where he is now laid to rest.

Sources: Plan of Buildings at Mount St. Vincent, Fourth Division—Central Park (Bacon 1856); New York County Conveyances, Vol 467, p520-522, Vol 489 p212-214, Vol 485, p207-208, Vol 668, p256-258 “United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975,”FamilySearch; “Morland Micholl,” The Asmonean, Apr 22, 1853; “Special Notice,” The Asmonean, Oct 27 1854; “Monument to the late Morland Micholl,” The Asmonean, Nov 3, 1854; “The Cemeteries,” The Asmonean, Feb 22, 1856; “Shaaray Tefilla and the Cemetery Question,” The Asmonean, Jul 4, 1856; “The Cemetery Question,” The Asmonean, Aug 29, 1856; “Auditor’s Report: Congregation ‘Gates of Prayer,’” The Jewish Messenger, Jun 5, 1857; A Preliminary Historical and Archaeological Assessment of Central Park to the North of the 97th Street Transverse…(Hunter Research, Inc.1990); Shaaray Tefila: A History of its Hundred Years, 1845-1945 (Cohen 1945); National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form—Beth Olam Cemetery, Jan 2016; “Prepare for Death and Follow Me:”An Archaeological Survey of the Historic Period Cemeteries of New York City (Meade 2020)