African Americans have been a part of the heritage of the Bronx since 1670, when slaves were brought from Barbados to live and work on the estate of the wealthy and aristocratic Morris family. Free and enslaved blacks were integral to the borough’s development, constituting between 10 and 15 percent of the area’s population during the colonial period. Before the end of slavery in New York in 1827, most blacks in the Bronx were buried in plots set aside for them on the estates of slave-holding families. In 1849, a group of black men formed the first African American church in the Bronx and, alongside it, the only independent African burial ground known to have existed in the borough.

In the 1840 census, 187 African Americans were among the 4,154 residents of the Town of Westchester (now part of the East Bronx). Blacks worshipped, were baptized, married and buried at the town’s St. Peter’s Episcopal Church or elsewhere, but they had no place in the town where they could serve in leadership roles or have their own burial grounds. To remedy this, the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Westchester formed in 1849 and a year later acquired a 1.25-acre parcel on what is now Unionport Road.

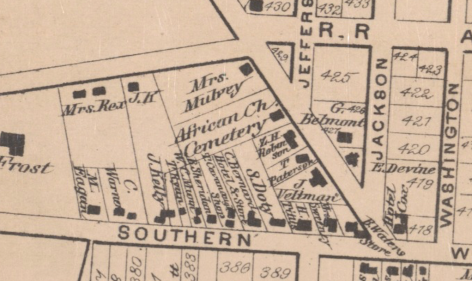

The congregation built their church, known as Bethel A.M.E., at the southeast corner of the parcel, and used the land behind the building as a cemetery. The church and adjacent cemetery were situated at a provincial commercial center convenient to a good number of African-American laborers, skilled craftsmen, and service professionals who worked on the estates of the East Bronx or in area businesses. But by the late 1800s, Bethel A.M.E. struggled to survive—although the congregation reincorporated as Centreville African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1888, in 1894 they sold the property and disbanded. Chang Li Supermarket occupies the site today.

At least 58 individuals were interred in the Bethel A.M.E. church cemetery between 1850 and 1894. Prior to disposing of the church property, the trustees had the remains in the cemetery exhumed and reinterred in a plot they acquired at Mount Hope Cemetery in Westchester County. The Bethel A.M.E. plot at Mount Hope is marked with a large monument commemorating the congregation’s history. The memorial is inscribed: “Bethel A.M.E. Church of Westchester, New York. Founded by Rev. Stephen Amos, dedicated Mar 11, 1849. Elders Rev. Ely N. Hall, Rev. Jas. M. Williams. Trustees Uriah Copeland, Thos. Chapman, Jno. G. Mickens, Benj. States, Hy. Jackson, Jno. Francis, Eppenetis Treadwell.”

Among those buried in the Bethel A.M.E. cemetery were several members of the Mickens family of West Farms. John Mickens, a church trustee, was a laborer originally from Maryland who, with his wife Charlotte, purchased a parcel of land in the Town of West Farms in 1850. John’s son, also named John, was a waiter who lived in separate household in West Farms with his wife Julia, a dressmaker, and their children. The younger John Mickens was interred at Bethel A.M.E. cemetery in 1867; his headstone, standing in the church’s plot at Mount Hope Cemetery, is one of the few intact markers surviving from the original cemetery.

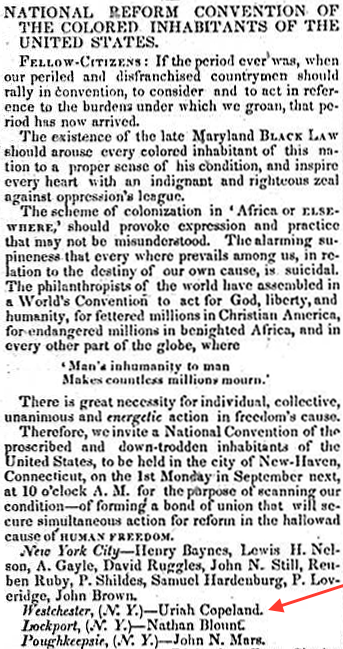

Some of the earliest burials in the Bethel A.M.E. cemetery were eight children of Uriah and Zilpah Copeland, interred there between 1849 and 1852. Uriah Copeland, a Virginia native who lived with his family in the Town of Westchester in the 1840s and 1850s, was a founding trustee of Bethel A.M.E. He also is notable as an associate of David Ruggles, the leading African American abolitionist of antebellum New York City. Copeland’s name appears alongside Ruggles’ in notices published in several national anti-slavery newspapers. They were among the men who announced the “National Reform Convention of the Colored Inhabitants of the United States of America” to be held in New Haven, Connecticut, in September 1840 to form “a bond of union the will secure simultaneous action for reform in the hallowed cause of human freedom.” Later that same year, Copeland was on the committee “introducing to favorable notice” the Mirror of Liberty, an African-American magazine edited and published by Ruggles.

Uriah Copeland made his living as a farmer and carpenter and in the late 1850s he managed the Benjamin S. Collins estate in the Town of Pelham. In the 1860s, Uriah and Zilpah Copeland relocated to Providence, Rhode Island, with their surviving children. Broken tombstones marking the gravesites of the children they lost when they lived in the Bronx remain in the Bethel A.M.E. plot at Mount Hope Cemetery. These poignant relics mark short lives and convey loss, but also serve as reminders of the family’s role in local history and provide links to the early African American church and cemetery that they helped establish.

View more photos of the Bethel A.M.E. reburial plot at Mount Hope Cemetery

Sources: Beers’ 1868 Atlas of New York and Vicinity, Pl. 16; Cemeteries of the Bronx (Raftery 2016), 24-27; Blacks in the Colonial Bronx (Ultan 2012); “Plants and People, Remembering the Bronx River’s African-American Heritage,” Bronx River Sankofa, March 6, 2014; “National Reform Convention of the Colored Inhabitants of the United States of America,” The Liberator, Jul 10, 1840, 2; “The Mirror of Liberty,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, Nov 5, 1840, 87; “Country Seat to Let or For Sale” New York Times, Apr 15, 1858; Ancestry.com