And my son Israel shall allow and set apart a piece of ground 4 rods square, lying in the field, called Hedden field, for a burying ground for myself and family forever, and I do except and reserve the same as I have showed him, and do order him and his to grant the liberty to pass and repass through my farm to the same.

With this clause in his last will and testament of February 25, 1775, Nathaniel Underhill (1690-1775) instructed his son Israel to preserve the family burial ground on their farm in what is today the Williamsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx. Nathaniel was a grandson of Captain John Underhill, an early English settler and soldier in New England noted for his role in the Pequot War (1636-37), who eventually settled in Long Island. Nathaniel’s father, also Nathaniel (b. 1663), was the founder of the Westchester branch of the family, moving from Long Island and establishing a farm in what was then a southern part of the county. The elder Nathaniel is thought to have been the first to set aside land as a family burial ground on the Underhill farm at Williamsbridge, and may have been buried there.

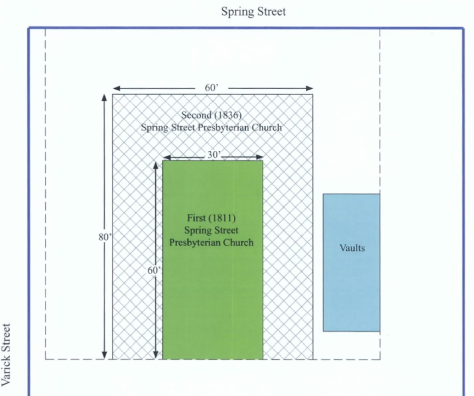

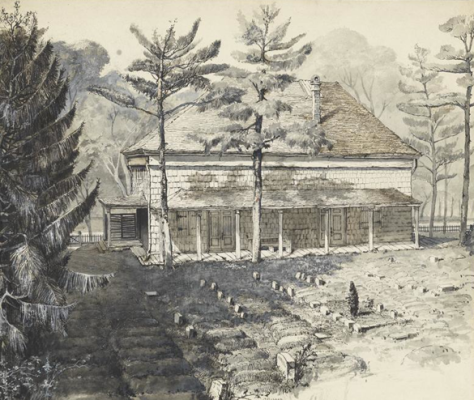

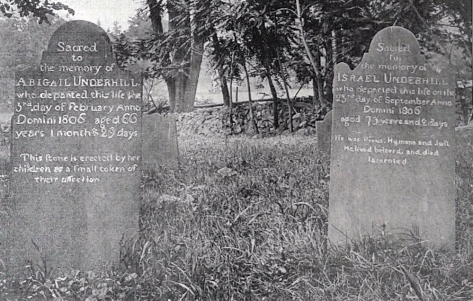

In 1812, the Underhills conveyed their lands at Williamsbridge to the Lorillard family and by the late 19th century the burial ground, largely forgotten and “going to decay from neglect,” was part of what was known as the Lorillard-Spencer Estate. Interest in the family cemetery at Williamsbridge was revived with the creation in 1892 of the Underhill Society of America by descendants of John Underhill. In August 1901, members of the Society visited the burial ground, where they located 16 graves in a plot measuring 60 feet on its west and east sides and 57 feet on its north and south sides. The oldest gravestone was that of Nathaniel Underhill, who earmarked the cemetery in his 1775 will. His tombstone, which featured a winged cherub’s head, was inscribed, “Here Lyes the Body of Nathaniel Underhill Was Born August the 11 1690 And Departed This Life November The 27 1775 Aged 85 Years, 3 Months, and 16 Days.” The most recent tombstones were those of Nathaniel’s son Israel and his wife Abigail, both of whom died in 1806. Society members took three photographs of the burial ground during their 1901 visit—the only known images to document the site.

The City of New York seized most of the Underhill burial ground property in 1913 for the extension of 205th Street (today’s Adee Avenue), with financial compensation paid to an Underhill family association. Members of the Underhill Society, incorporated as Underhill Westchester Burying Ground, Inc., acquired a 100’ x 40’ lot at the northwest corner of Adee Avenue and Colden Avenue that contained what was left of the burial ground. In 1916, in anticipation of the street extension, the Underhill Society reported that graves in the portion of the burial ground that had been taken by the city would be moved to the lot at Adee and Colden avenues. A history of the Underhill family compiled in the 1930s states that remains from the burial ground were removed to the cemetery at St. Paul’s Church in Mount Vernon, where some Underhill family members worshipped in the 18th century. However, local historians and preservations believe that, although tombstones from the site were moved to St. Paul’s ca. 1920, the graves are still in the parcel at Adee and Colden avenues.

Three sandstone burial markers from the old family cemetery—those of Nathaniel Underhill and his son Israel (both mentioned above), as well as that of Anne Underhill, who died in 1786—are preserved at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site, where they are mounted to the exterior southern wall of the bell tower. Since 1989, the city’s Department of Citywide Administrative Services has owned the parcel at Adee and Colden avenues. A chain-link fence encloses the site but there is nothing to indicate it is “the burying ground forever” of a prominent colonial-era family.

Sources: Bromley’s 1881 Atlas of Weschester County, Pl 44-45; Abstracts of Wills on File in the Surrogate’s Office, City of New York, Vol 8, 1771-1776 (NY Historical Society 1899), 320-321; Annual Reports of the Underhill Society of America, 1897-1916; Underhill Genealogy, Vol 2 (Frost 1932), 64-65, 87-89, 119-121; Burial Markers from the 18th Century Installed at St. Paul’s Church in the 20th Century, St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site, December 2014; Cemeteries of the Bronx (Raftery 2016), 247-255