In 1908, the New York Tribune published the following verse from a poem entitled “A Visit to the Old Home”:

I stood within the graveyard, boys, Among loved ones at rest; And peered within the marble vault Where lay our friends the best. The Reverend Father Dougherty And “Father John” Drumgoole, Whose minds and hands both worked and planned To teach the Golden Rule.

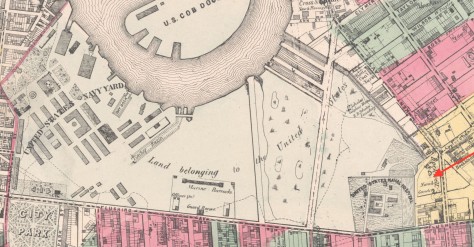

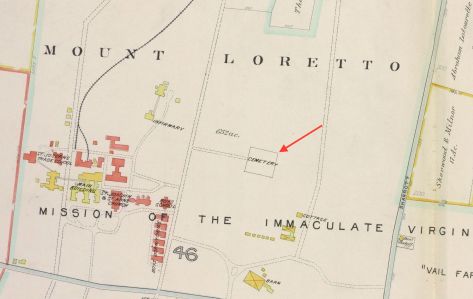

The Tribune reprinted this stanza from the December 1908 issue of the Mount Loretto Messenger, the class journal of the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin of Mount Loretto, which was dedicated that month to the 25th anniversary of the Mission’s opening on the south shore of Staten Island. The Mission of the Immaculate Virgin was founded in 1883 by Father John C. Drumgoole as a facility to house and train homeless boys. Operated by the Archdiocese of New York, the main buildings were located north of present-day Hylan Boulevard and west of Sharrott Avenue. Girls were admitted beginning in 1897 and lived in St. Elizabeth’s, a Victorian building on the south side of Hylan Avenue.

By 1947, the facility at Mount Loretto spread over 700 acres and had 42 buildings—including the Church of Sts. Joachim and Anne— that housed 700 boys, 360 girls, 85 Franciscan nuns, and five priests. By that time, it had been the home of over 50,000 children and was the largest childcare institution in the U.S. As foster care emerged and orphanages declined, Mount Loretto transitioned in the 1970s. The Mount Loretto campus, much reduced in size, is now run by Catholic Charities of Staten Island and is home to numerous educational, athletic, and service programs that aid children and teens, the disabled, and those living with addiction and mental or physical challenges.

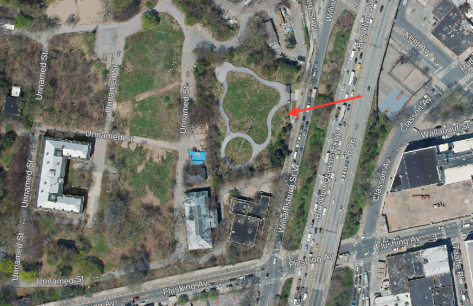

The poem quoted above was written by Thomas J. Reynolds, one of the former “mission kids,” and describes a visit to the cemetery at Mount Loretto. The small graveyard is located in a clearing in the woods at the back of the Mount Loretto grounds, down a road east of the main buildings. The earliest known interments here were husband and wife Louis and Louise De Comeau in 1885. The De Comeaus were a wealthy local family that made generous contributions to the Mission. Their daughter Yolande donated $100,000 for the construction of a home for blind girls on the property. She later joined the Sisters of St. Francis and became Superioress of the motherhouse at the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin in 1900.

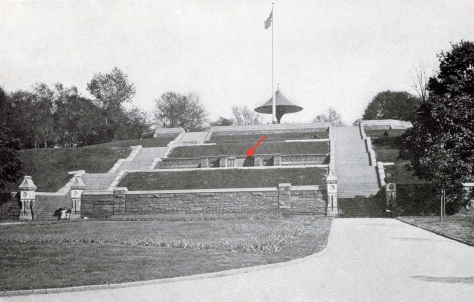

Father Drumgoole was buried in Mount Loretto Cemetery when he died of pneumonia in 1888. In 1899 his body was moved from his grave to a mausoleum built by his close friend and successor as head of the Mission, Rev. James J. Dougherty. Rev. Dougherty is also laid to rest in the tomb, which stands on a gentle rise in the center of the cemetery. Msgr. Mallick J. Fitzpatrick, who headed the Mission from 1907 until he died in 1936, is interred beside his predecessors.

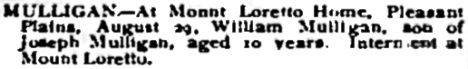

Mount Loretto Cemetery is the final resting place for children who died in the facility and for alumni raised at the Mission who died after they went out into the world but were returned to their old home for burial. Notable among these is U.S. Marine Angel Mendez, who was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross. In 1967, during the Vietnam War, Mendez died saving the life of his platoon commander Ronald Castille, who would later become the Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

Dozens of rows of simple, flat headstones at Mount Loretto Cemetery mark the graves of the Franciscan nuns who taught at the Mission. Among them is the grave of Sister Mary Angela Flanagan, a Superioress of St. Elizabeth’s, the girl’s home at Mount Loretto. She died at age 40 of burns she received when candle flames ignited her robes as she knelt before a shrine for prayers on a December night in 1898. The Mount Loretto Cemetery is still actively used for interments of Sisters of St. Francis who were formerly connected with the Mount Loretto campus. One of the most recent burials is Sister Mary Beatrice Campbell, who entered the Order of St. Francis in 1928 and taught at the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin from 1937 to 1945. She died in 2015 at age 105.

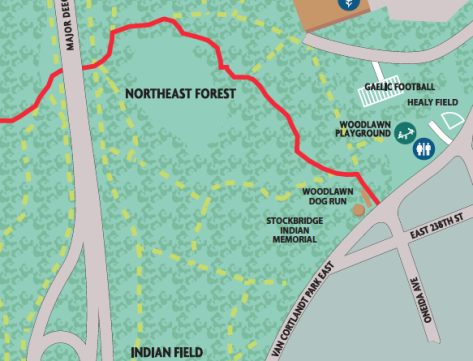

Today the old graveyard at Mount Loretto is maintained by staff of Resurrection Cemetery, which is located just east of the Mount Loretto campus and was created in 1977 from a large swathe of land transferred from the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin. Few know of the cemetery’s existence at Mount Loretto; no signs point the way to this historic burial ground beyond the modern school buildings and athletic fields. And those who stumble across are out of luck; it is protected by an iron fence and gate that is kept locked with a “no trespassing” sign warning away intruders.

But the cemetery does have occasional visitors. Each September, alumni return to Mount Loretto to reunite and reminisce on the grounds of the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin. The cemetery is a favorite spot for the former “mission kids” and their families to visit on these annual Alumni Days, offering them a time to reflect on the hallowed ground where the Mission’s founder is laid to rest, along with others who served at the Mission or were raised there.

Sources: Robinson’s 1907 Atlas of the Borough of Richmond, City of New York, Pl 21; Children’s Shepherd: The Story of John Christopher Drumgoole (Burton 1954); Realms of History: The Cemeteries of Staten Island (Salmon 2006); “The Death of Mrs. De Comeau,” New York Herald, Dec 15, 1885; “Father Drumgoole’s Funeral,” New York Herald, April_3_1888; “These Boys Get Along,” The Sun, May 11, 1890; “Nun at Prayer Mortally Burned,” New York Herald, Dec 7, 1898; “Father Drumgoole’s Body Moved,” New York Tribune, Dec 1, 1899; “Death Notices,” Richmond County Advance, Sep 6, 1902; “Its Silver Jubilee,” New York Tribune, Dec 10, 1908; “Msgr Fitzpatrick Buried on Monday,” The Tablet, Dec 12, 1936; “A Push to Get Staten Island War Hero the Medal of Honor,” Staten Island Advance, Mar 16, 2009; “Sister Mary Beatrice Campbell, O.S.F.,” Catholic New York, Jul 9, 2015; “’Mission Kids for Life’ Reunite and Reminisce at Mount Loretto,” Staten Island Advance, Sep 24 2017; “Mount Loretto” Staten Island Advance, May 15, 2018; Hidden Staten Island: Exploring the Secrets of Mt. Loretto