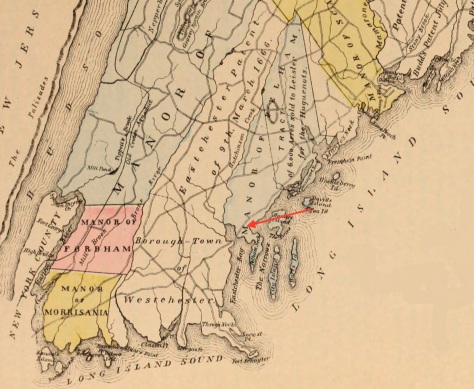

When I received a Pell Grant as an undergraduate pursuing an anthropology degree at the University of Arkansas in the early 1990s, I didn’t imagine that I would one day wander down a remote wooded path in the Bronx in search of a tiny cemetery where Pell ancestors are buried. Pell Grants are named in honor of former U.S. Senator Claiborne Pell (1918-2009), whose forefather Thomas Pell bought a large tract of wilderness from a council of Native American sachems in 1654. The British crown later granted Thomas Pell a royal charter for this 9,000-acre expanse, named the Manor of Pelham, that covered parts of what is today the Bronx and Westchester County. With this land grant, the seed was planted from which grew a dynasty that has had far-reaching influence throughout American history.

The Pell family burial ground is located just southeast of the Bartow-Pell mansion, built between 1836 and 1842 by Robert Bartow, a Pell descendant. The house and burial ground are on land that was part of the ancient Manor of Pelham and, except for a brief period, this property was in the hands of Pell descendants for 234 years before the city acquired it in 1888 to become part of Pelham Bay Park. Six tombstones dating from 1748 to 1790—including one for Joseph Pell (d. 1752), the Fourth Lord of the Manor of Pelham—are enclosed in this plot of roughly 100 square feet near the Sound at Pelham Bay. The cemetery’s location on ancestral land made the burial ground a venerated site for the Pell family; they added a large memorial stone in 1862 and a fence with inscribed granite posts in 1891.

After Thomas Pell died in 1669, his descendants began to sell off pieces of his manor and its acreage shrank. The American Revolution brought an end to the Pell lordship and manor—members of the family being Loyalists, they fled to Canada for British protection. They were disgraced and their property was confiscated. Their original manor house, located near where the Bartow-Pell mansion now stands, was burned. But their exile was temporary—once political passions cooled, the Pells returned to New York and resumed their prominent place in society.

The old Pell cemetery has been a historical attraction since the city acquired it, and in 1905 was deemed “one of the most interesting nooks of the beautiful and immense Pelham Bay Park” by a local newspaper. The cemetery also has occasionally attracted visitors with nefarious intentions. Acting on a legend that says the plot contains gold and jewels hidden by the Pells, thieves have periodically tampered with the graves in their search for booty. One such case occurred in 1914 when police found a fresh hole dug five feet deep in the burial ground. Further evidence suggested that the bandits had been at work on another grave at the site before they were frightened away.

In 1988, the Pells had a family reunion at the Bartow-Pell mansion. As part of the festivities, the relatives walked down the short path bordered with horse chestnut trees to inspect graves in the ancestral burial ground. Claiborne Pell, a descendant of the original lords of the manor, was an attendee at this reunion. Like his relatives, he had a great appreciation for the place of his ancestors in colonial history and understood that he was raised as American nobility. Though he was born into privilege and vast family wealth, Claiborne Pell envisioned a grant program that would enable low-income students to attend college. As a recipient of this program, a Pell Grant helped put me on a career path that would eventually lead me to New York, and, consequentially, to the Pell ancestral graveyard. Mine is one of countless examples of the ways we are intertwined with—and indebted to—those who have gone before us.

View more photos of Pell Family Burial Ground

Sources: Map of the Manors Erected Within the County of Westchester: Compiled from the Manor Grants and Ancient Maps (De Lancey 1886); History of the County of Westchester (Bolton 1848); The History of Several Towns, Manors and Patents of the County of Westchester, Vol 2 (Bolton 1881); History of Westchester County,Vol 1 (Scharf 1886); “Where the Pells Lie,” New York Tribune, Dec 6, 1903; “Where the Pells Lie,” [Letter to Editor], Dec 27, 1903; “Old Historic Cemeteries,” Daily Argus (Mount Vernon, NY), Jan 9, 1905; “Ghouls Try to Rob Old Pell Graves,” New York Tribune, Oct 31, 1914; “Pell’s Grave Violated,” New York Times, Oct 31, 1914; The Pell Manor: Address Prepared for the New York Branch of the Order of Colonial Lords of Manors in America (Pell 1917); A Brief, But Most Complete & True Account of the Settlement of the Ancient Town of Pelham…(Barr 1947); National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form—Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum, 1974; “Claiborne Pell, 90, Patrician Senator Behind College Grant Program, Dies,” New York Times, Jan 2, 2009; We Used to Own the Bronx: Memoirs of a Former Debutante (Pell 2009); Pell Family Burial Plot—Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum; Here Lyes the Body: The Pell Family Burial Ground, Mansion Musings, Oct 22, 2016; Cemeteries of the Bronx (Raftery 2016)