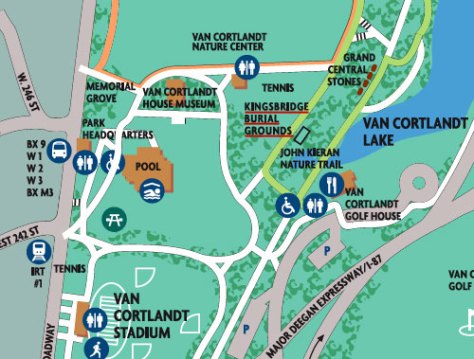

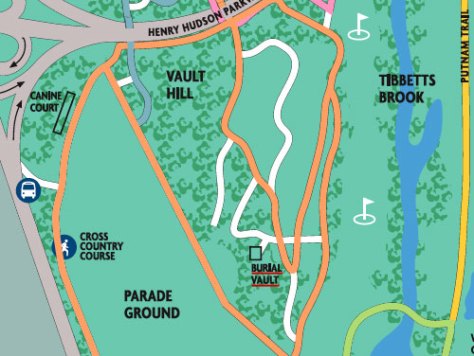

In 1694, Jacobus Van Cortlandt acquired a tract of land in “Lower Yonkers” that became the nucleus of what is now Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. Jacobus was the youngest son of Oloff Van Cortlandt, a wealthy Dutch merchant who founded the Van Cortlandt dynasty that was influential in New York from the colonial period into the 19th century. Jacobus added to his estate throughout his lifetime and in 1732 acquired the tract upon which his son Frederick built a family home in 1748-49. Frederick fell ill and died during completion of the house in 1749, and his will directed that he be buried in “a Family Vault which I intend to Build on my plantation on a little Hill which lies to the Northeastward of Tuttle Brook.” This burial vault was completed shortly after Frederick’s death and was used as a family burial ground until the Van Cortlandt estate was acquired for a city park in 1888.

The Van Cortlandt burial vault is situated atop a steep ridge that became known as Vault Hill. The site gained renown in 1776 when Augustus Van Cortlandt, Frederick’s son who was then New York City Clerk, hid the city records in the family burial vault to protect them from destruction during the British occupation of New York in the American Revolution. A fieldstone wall surrounds the burial ground but most of the headstones and markers were removed when the site was vandalized in the 1960s.

Sources: The Story of the Bronx (Jenkins 1912), 301-302; “Van Cortlandt of Lower Yonkers,“ New York Genealogical & Biographical Record 5(4):168-171; “Indian Fields Now a Park,” New York Herald, Sept 29, 1895; “City’s Last Colonial Estate to be Sold,” New York Times, Sept 21, 1919; “Van Cortlandt’s Plot Neglect,” New York Times, Oct 1, 1962; Van Cortlandt House Museum; New York City Parks Dept.; Van Cortlandt Park Conservancy; Museum of the City of New York.