An early 20th century guide to New York City cemeteries describes Calvary Cemetery in Queens as “by far the most important burial ground in the vicinity of New York, and, in fact, in the United States in point of interments, extent and the number of monuments and headstones that go to make it a wilderness of rising tombstones.” With an estimated three million burials, today it is America’s largest cemetery in number of interments and is renowned for its dramatic setting—a vast necropolis tucked in among the chaotic surroundings of highways, industrial buildings, and businesses, with views of Manhattan rising as a backdrop.

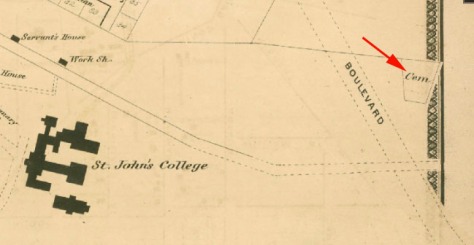

The Archdiocese of New York established Calvary Cemetery in 1848 after the closure of their burial grounds at St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral and on 11th Street in Manhattan. Located in the Long Island City/Woodside area of Queens and managed by the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Calvary served as the main burying ground for Manhattan’s Roman Catholic population for many years and burials are still made there. By the early 1900s, it had over 750,000 interments and handled 18,000 burials a year—almost half the annual deaths in the city at that time. Calvary’s 365 acres hold five times as many bodies as the more famous and spacious Green-Wood Cemetery in nearby Brooklyn and are divided into two expanses: Old or First Calvary, the cemetery’s earliest parcel, bounded by the Long Island Expressway, Laurel Hill Blvd, Review Ave, and Greenpoint Ave; and New Calvary, three divisions stretching from Queens Blvd to 55th Ave and cut by the Long Island Expressway and Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Calvary’s scenic power results from the magnitude of graves and tombs and the surrounding presence of urban life rather than from its design; however, Old Calvary does contain several significant monuments and features. The charming red brick, Queen Anne-style gatehouse at the main entrance (Greenpoint Ave at Gale Ave) is an architectural gem, one of the last of its kind in the area. At the center of the grounds is the cemetery’s chapel, which was declared the “most remarkable mortuary chapel in America” when it was erected in 1908. Designed by architect Raymond F. Almirall, it features a beehive-shaped concrete dome crowned with a statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Crypts below the building are for the burial of priests of the Archdiocese.

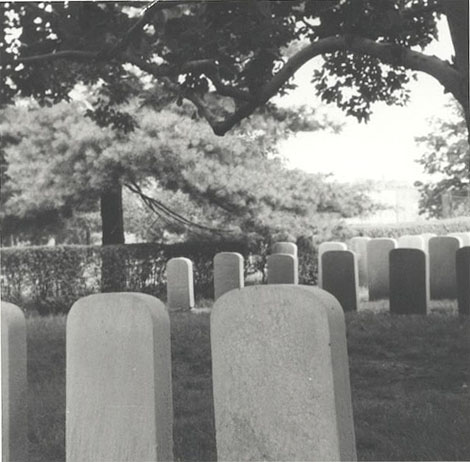

In the southeastern part of Old Calvary, a Civil War monument erected by the City of New York in 1866 honors 21 Roman Catholic Union soldiers interred in a 40×40 foot plot that is a city-owned park within Calvary. The 50-foot-high granite obelisk is surmounted by a bronze figure representing peace that was sculpted by Daniel Draddy. Draddy also created the four life-size bronze figures depicting Civil War soldiers that stand on pedestals surrounding the column (identical figures border the Soldiers’ Monument at Green-wood Cemetery, which was erected three years later). Adjacent to Calvary’s Civil War monument is a memorial to New York City’s famed Fighting 69th Infantry Regiment of the New York Army National Guard. Formed in 1849, this Irish-heritage unit gained notoriety for its members’ bravery and valor in the Civil War.

Near the Civil War/69th Regiment plot is a metal fence enclosing a “cemetery within a cemetery”—a small burial ground that predates Calvary Cemetery. When the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral were assembling land to form Calvary in 1845, they purchased a tract from Mrs. Ann Alsop, part of a farm that had been in the Alsop family for generations and included the old family graveyard. When the property was sold, the agreement provided that the Alsop family burial ground would remain inviolate and the Trustees have maintained it to this day. About 30 gravestones stand in the old burial ground, dating from 1718 to 1889.

The showpiece at Old Calvary is the massive Johnston mausoleum that sits atop a hill near the cemetery’s eastern edge. Built of huge granite blocks, this domed neo-Baroque chapel and tomb has a figure of Christ holding a cross at its summit and sculpted angels at each corner of the roof, gazing heavenward. Magnificent but blackened by age and pollution, with a decaying marble frieze above its fragmented bronze ornamental doors, it has an atmosphere of neglect and dissipation that is a visible symbol of the rags-to-riches-to-rags story of the family that reposes within.

John Johnston, head of the dry goods firm J. & C. Johnston, was one of the city’s most successful merchants when he built the mausoleum in 1873, reportedly at a cost of $200,000 (roughly equivalent to $4 million today). Born in Ireland in 1834, Johnston came to New York in 1847 and worked his way to the top of the mercantile trade. His successful dry goods firm included brother Charles Johnston, who died in 1880. John bore a deep affection for his brother Charles and never recovered from the latter’s death; he died in 1887, leaving the family fortune and business in the hands of his younger brother, Robert Johnston. The once-thriving firm closed a year after John’s death and Robert gradually lost the family millions as well as his palatial home along the Hudson River in Riverdale. He spent his final years in poverty, living as a recluse in a barn on his former estate. Robert was found there in 1904, sick with pneumonia and insane, and died in the hospital at Ward’s Island. He was interred alongside his brothers in the family crypt.

A number of notable individuals are also buried at both Old Calvary and New Calvary, including Olympic gold medalist Martin Sheridan, considered the greatest all-around athlete of his time; Annie Moore, the first immigrant processed through Ellis Island; Joseph Petrosino, a trailblazing NYPD detective who was a pioneer in the fight against organized crime; and four-time New York governor Al Smith, the first Roman Catholic to run for United States president (in 1928). Moreover, Calvary is legendary as the fictional burial site of Vito Corleone in The Godfather. One determined urban explorer has identified the exact spot in the cemetery where the burial scene was filmed for the 1972 Mafia classic: Old Calvary, Section 1W, Range 18, Plot P, Grave #17.

View more photos of Calvary Cemetery

Sources: Calvary Cemetery; Beers 1873 Atlas of Long Island, Pl 52; The Cemeteries of New York (Judson 1881), 3; History of Queens County, New York (Munsell 1882), 379; King’s Handbook of New York City (1893), 522; The Leonard Manual of the Cemeteries of New York and Vicinity (1901), 16-19; “New Catholic Cemetery,” New-York Freemans Journal and Catholic Register Aug 5, 1848; “The Catholic Cemeteries of New York,” Historical Records and Studies 1 (1899), 375-377; Silent Cities: The Evolution of the American Cemetery (Jackson & Vergara 1989), 34-35; Encyclopedia of New York City (Jackson 1991), 176; 300 Years of Long Island City (Seyfied 1984), 179-180, 183; “You Can Come and Go. They’re Staying Awhile,” New York Times Nov 30, 2008; “A Protestant Burial Ground Maintained by Catholics,” New York Times Apr 12, 1950, 29; AIA Guide to New York City (White et al 2010), 765; “Most Remarkable Mortuary Chapel in America,” Popular Mechanics Sep 1909, 292-293; “Burial of Charles Johnston,” New York Tribune May 4, 1880, 8; “An Old Merchant Dead,” New York Times May 17, 1887; “Poor, but has a $200,000 Tomb,” The Sun May 10, 1903, 3; “Once Rich, Now in Morgue,” New York Times May 4, 1904; Calvary Cemetery, Queens New York Est 1848 (aerial video); NYCityMap